REVISTA N° 17 | AÑO 2017 / 2

Resumen

Madres inmigrantes: el conflicto de pertenencia al viejo y al nuevo mundo y las relaciones en la nueva familia

En dos parejas, constituidas por un marido y una mujer extranjera de reciente inmigración (en un caso de Brasil, Estela; en el otro de la Repứblica Checa, Aneta) se puede observar una dinámica de identificación proyectiva por parte de la madre hacia el hijo pequeño, mientras que su pareja responde a lo que hace la mujer de manera muy diferente.

Las dos mujeres viven un conflicto entre la nostalgia por el pasado y la necesidad de acostumbrarse al nuevo país: este doloroso conflicto se escinde, y una parte de él se proyecta sobre el hijo. Estela parece proyectar sobre la hija de 3 años la necesidad de ajustarse rápidamente a la realidad, y exige que su hija sea “autónoma”. Aneta parece proyectar sobre la hija la necesidad de una relación simbiótica y “separada” respecto de su entorno; la hija, de seis meses, sólo se queda con su madre día y noche, y la mujer no puede volver a trabajar.

La actitud de tolerancia hacia la mujer y la hija de parte del marido de Estela facilita la evolución de esta situación; la rigidez del marido de Aneta, basada de la misma manera en sus necesidades inconscientes, quien exige que su hija se quede con otras personas, contribuye en bloquear la situación.

Palabras clave: migración, relación madre-hijo, identificación proyectiva, relación de pareja, utilizo de un instrumento simbólico

Résumé

Mères immigrées: le conflit d’appartenance au vieux et au nouveau monde et les relations dans la nouvelle famille

A l’intérieur de deux couples composés d’un mari italien et d’une femme étrangère récemment immigrée – l’une du Brésil, Estela, et l’autre de République Tchèque, Aneta – on peut remarquer une dynamique d’identification projective de la mère envers l’enfant tandis que le mari répond à l’attitude de sa femme d’une façon très différente. Les deux femmes vivent un conflit entre la nostalgie du passé et la nécessité de s’adapter au nouveau pays. Ce douloureux conflit est clivé et une partie est projetée sur l’enfant. Estela semble projeter sur sa fille de trois ans le besoin de s’adapter vite à la réalité et pour cela elle exige que la petite soit précocement “autonome”. Par contre Aneta semble projeter sur sa fille la nécessité d’une relation symbiotique séparée de la réalité qui l’entoure: la petite de six mois veut être seul avec sa mère, le jour comme la nuit, et la femme ne peut pas reprendre son travail. L’attitude bienveillante du mari d’Estela envers sa femme aussi bien qu’envers sa fille aide l’évolution de la situation; la rigidité du mari d’Aneta, fondée sur sa dynamique inconsciente qui exige que sa fille soit avec d’autres personnes, contribue à bloquer la situation.

Mots-clés: migration, relation mère-enfant, identification projective, relation de couple, emploi d’une figure symbolique.

Summary

Mothers who have migrated: reconciling their past with the demands of new family relationships

Two comparable vignettes are discussed which illustrate the dilemma of mothers who have migrated and who are trying to reconcile their past with their new roles in families in different cultures. Both mothers (Estela and Aneta) struggle with homesickness and with the necessity of adapting to a new country as wives and mothers. In both cases this painful conflict is split off and projected onto their daughters (projective identification). Estela, who migrated from Brazil, appears to project onto her daughter her own need to adapt to the new culture, whereas Anita, who migrated from the Czech Republic, seems to project her need for a symbiotic relationship that functions to separate her from her current painful reality. In each case their husbands react in different ways. Estela’s husband facilitates his wife’s adaptation to her new situation, while Aneta’s husband, who demonstrates less flexibility due his own unconscious needs, stymies his wife’s adaptation. In terms of therapeutic action, the development of symbolic representation assists the empathic identification which is necessary for growth to occur.

Keywords: migration, mother-child relationship, projective identification, couple relationship, symbolic representation.

ARTÍCULO

Introduction

When people emigrate to another country they live the traumatic loss of their usual landmarks, that gave them safety up to that moment (Sandler, 1960): not only the people whose memories and deep affection they are linked to, but objects, sights, smells, colours, climate, language, culture, habits are also lost.

Migration therefore involves the break of life continuity and the loss of contact with significant people and places. In this way, migration is a traumatic event that marks forever a “before” and “after” in the life of a migrant: such breach of continuity determines a process of deconstruction-reconstruction of the self-representation and thus a “fracture” of relationships with others. The emigrant, in an unstable balance between the reality of departure and that of arrival, risks to be «a prisoner of both worlds and alien to both: extraneous to his/her past and alien to the present-future, suspended between two worlds» (Nathan T., 1996, p. 57), developing, if the conflict is too acute, various kinds of symptoms.

The need to assimilate themselves at least in part to the arrival culture may indeed be seen by some people as a threat to their own identity, so it may be opposed by feelings of guilt and inadequacy that feed the opposite desire to remain firmly clinging onto their roots, rejecting any update of roles and relational modalities of the past. On the contrary, for others it may be a strong desire to quickly adapt to the arrival environment, defending themselves from the feeling of extraneousness through a more or less effective attempt at camouflage.

The balance between these opposing tendencies is different for different people, because their perceived obligation to their family mandate, their adaptability and, more generally, their ability to integrate different aspects of self may be different. So the couple’s and family’s dynamics of migrants are struck not only by the encounter or clash with the unknown external reality, but also, so to speak, from the inside of the family relationships. Also the experience that immigrants’ children live, through their school attendance and the inevitable socialization with peers, may create tensions and imbalances in the family, because the child ends up playing the role of “translator”, able to enter into a dialogue with instances of the new culture, while the immigrant parent cannot easily do so (Moro, Neuman, Réal, 2010).

Finally, for an immigrant woman, pregnancy and childbirth in the new country reactivate the trauma of detachment, first of all because this event – one of the most significant of her life – is lived without the safety net of the family ties of belonging, particularly the women’s one. Secondly, during pregnancy the double identification process – on the one hand with the young baby the woman had once been and with the baby that she would have wanted to be; on the other hand with the parents that she has had and with those who she would have liked to have had (Darchis, 2009) – recreates the trauma of loss, which returns with more force. «So the birth, the moment of the breaking of the maternal – physical and psychic – wrapper is often found as a factor which reactivates the suffering of exile» (Moro, Neuman, Réal, 2010, p. 17).

Initially the therapist can intervene in this situation by offering a recognition of the immigrants suffering, the first step to make it possible for them to begin to mourn their loss: their journey narration, their past memories and the items that they may have brought with them facilitate the transcription and preservation of what has been lost in symbolic terms.

«According to Freud (1917), the mourning process is work developed by the psyche to face the loss or death of a significant object, in order to re-introject into the ego the different kinds of links with that lost object, and to be able to resign oneself to accepting that reunion will not happen» (Losso and Packciarz Losso, 2006, p. 121).

Only through the creation/activation of a symbolic dimension – different for each person and for each family – in which something of the past can be processed and kept, will it be possible for migrants to multiply “the going and returning” between the different worlds, as suggested by Moro (ibid.)

The ways in which immigrants prepare for their journey (the quality and the gradualness of their preparation) certainly affect their emotional and cognitive investment in the future scenery. But even when people emigrate in a “privileged status” – as in the two situations here presented – anyway the subjects may still have a strong conflict between the desire and need to integrate them into the new situation and the longing and regret for their country of origin and this conflict may affect their couple and family relationships.

Two clinical situations

Carlo and Estela

Estela came to Italy from Brazil to pursue a master’s degree in computer science at Bologna University, where she met her future husband, Carlo, who like her graduated in computer science. During the Masters she received a job offer and decided to remain in Italy. Soon after Carlo received an offer of an advantageous work in Milan and the two decided to get married and to move together to that city of Lombardy.

After a year, Estela becomes pregnant, and starts from the first month to have a very strong nausea, which will accompany her throughout her pregnancy, forcing her to have two hospitalizations and, finally, to an emergency cesarean section at the 8th month for preeclampsia. The urgency of cesarean has the consequence that Estela is alone with both the intervention and the subsequent hours, because her husband is returning from a job trip abroad, while Estela’s mother comes from Brazil only 15 days after. Estela will say later that only when she got pregnant did she realize it would have been impossible for her to return to Brazil for ever, because having a child would have further entrenched her family in Italy (maybe Estela tried to “throw up” this painful thought and the experience of ambivalence during her pregnancy?).

The couple ask the therapist for some help when Maria is nearly three years old, primarily because Estela cannot tolerate that her husband refers to the possibility of another child: just the idea of re-living the difficult period of pregnancy and childbirth is intolerable for her. The husband seems to understand his wife’s point of view, speaks of his desire for a second child but without insisting: “Me too – he says smiling – I am an immigrant, but I can see my family once a month, while we meet Estela’s parents only every two years”. A deep nostalgia of Brazil emerges as Estela’s talks, but she reports that when she returns to the town where she was born she now feels different from her family, so she repeats several times that she no longer feels at home neither in Italy nor in Brazil. Her husband adds that for him it would not be impossible to find work in Brazil, but not in the small town where Estela’s family lives, rather in Sao Paulo or Rio, three hours away by plane. “So it is useless to go there”, replies Estela.

The spouses also discuss why Estela does not want to leave Maria with the paternal grandparents even for a few hours, when they go to meet them in Bologna, while her husband attempts to find some marital space without their daughter. “I will not leave her, because my mother would also like to look after her, but she can not” says Estela, thus showing that it is the conflict of loyalty towards her own family that prevents her from using resources that are presently available. During the course of treatment, Estela accepts leaving her daughter with her parents-in-law in the afternoon and, after a few months, even at night, because her husband seems able to suggest changes, but also to respect his wife’s long, slow processing time needs.

The second problem the couple have to bear is the irritation of Estela with her daughter, now three years old, who refuses to pee and poop on the potty. The child has to go to the kindergarten in a few months, and Estela cannot tolerate that the child does not learn “in time, that is immediately. In Brazil, children are in the family, and it’s not so important if the three-year-old children still have the diaper, but here…”

The rigid attitude of the wife makes the couple argue, because her husband is, once again, in a more tolerant position and does not share the anxiety of his wife, and in turn gets upset with her. Estela’s refrain “Maria has to adapt herself” seems partly related to herself: it is as if she had put her own need to adapt herself to the Italian situation into Maria, through a projective identification, because of her intrapsychic fighting between her need of adaptation and her deep longing of Brazil, because of its – in her words – “emotional warmth”. This conflict, too sharp, is split and a part of it is “deposited” onto her daughter.

It is possible to feel Estela’s pain of not finding a possible way out of the impasse.

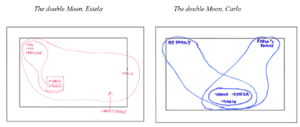

The therapist decides to propose the projective graphic tool The Double Moon (Greco, 1999; 2005; 2006; 2012), to help the couple better understand their experience with respect to their own family and cultural belonging, one of the most significant themes underlying to the difficulties of the couple and to the suffering of Estela.

In fact, in structurally complex family situations, not all the significant elements, with which subjects have an emotional connection to, are present in the “here and now” of their daily life. It is so for example for adoptive or fostering families or, as in this case, for migrants’ families.

It is very interesting to note that the term family is a polysemantic one and the clinical experience shows that different people interpret it according to the more current and critical significance for them in respect of their plural belongings.

It can be observed how Estela’s drawing reflects her loneliness – she draws herself alone, at the edge of the rectangle, and fosters the task of integrating the two memberships to her little Maria: that to the Italian family and the Brazilian one (from both of which she excludes herself).

Only with the magic wand, that is at her desire level, Estela draws a larger family circle that includes her too – even if always isolated – and Carlo’s family, which is approached and placed inside the rectangle.

Carlo’s protocol on the contrary shows his clear awareness regarding the distinction between his new family – he, his wife and their daughter – and the two families of origin, at the same distance from it.

So, Carlo offers his wife the exemplum of a possible mode of integration of the two roots. The dialogue that emerged from the comments to the two drawings helps Estela to understand that Carlo is affectionately close to her and to recognize her own difficulties, with which she can cope now more explicitly.

In the last session, Estela reports smilingly that Maria, who wanted a very elegant and light dress for a birthday party of a little friend of hers, realized that the diaper was visible, so she decided to leave it suddenly, and since then she uses the potty without any problem.

“She had to decide by herself” Estela comments, associating her daughter’s decision to her own request of individual interviews.

Aneta and Giorgio

Aneta, rheumatologist, 37 years old, meets Giorgio, manager of a small textile industry, 45 years old, in Brno, where he had gone to deal with a large order for goods to be exported.

The two decide to get married soon (afterwards Aneta will explain that the small city in which she had been living was choking her and she, when she was living in the Czech Republic, had imagined Italy as the place of freedom and creativity), and she agrees to move to Italy, in the apartment of Giorgio, located in a family building in which both Giorgio’s mother (widow 71 years old) and his brother, with his wife and their 7-year-old son, live.

Once in Italy, Aneta, who had worked in a hospital in south-eastern Czech Republic, is accepted in the specialization of physical medicine and rehabilitation, which, according to her, may open more job opportunities in this new country.

In the following year she becomes pregnant and Alexia will be born: “Alexia with X, as in Czech Republic” Aneta underlines.

Giorgio, as a manager for his company organization, works a lot and he says he is very tired, so even dealing with Alexia’s crying for an hour while his wife prepares dinner destroys him.

When the couple asks for a therapist, Alexia is six months old, and the couple quarrel a lot. According to them, their daughter “wants to be only with her mother, night and day”.

The baby is not able to remain even on the carpet or in her stroller for a few minutes: she must stay in her mother’s arms. In fact, the couple arrive with their daughter, usually asleep, but when she wakes up she remains only in her mother’s arms, with little interest in the soft toys on the carpet, the room with coloured drawings of children…

“It is always so, doctor” Giorgio says. For this reason, it is impossible for Aneta to resume her hospital specialization: “a real job, doctor, with impossible schedules” she comments.

Aneta accuses her husband of falling asleep at 9 pm, so there is no sex life with each other. “The reason is my tiredness” Giorgio replicates “you’re always there with Alexia, what would I stay awake for?”.

When his wife says she would like another child, Giorgio replies: “you want me dead!”.

Aneta seems to fight a battle to remain separate from both her husband’s family – in particular from her mother-in-law, whom she feels is very intrusive – and from the Italian reality in general, about which she criticizes the very long working hours (both hers and her husband’s) and the family culture (“My 45-year-old husband is a mama’s boy, we don’t do this in Czech Republic”). She says she is very disappointed: she certainly had not imagined a life similar to what she is leading at the moment! Her previous idealization of the Italian situation has turned into its opposite, and she becomes fiercely critical about it.

The more the husband wants to force Aneta to leave Alexia at the nursery and a few hours to his mother, the more the child is crying to leave her mother even for a few minutes.

Giorgio insists “because it is right that children go to the nursery”; his wife rather plans to send for her father from Czech Republic for a few months and the discussion between the two continues.

Giorgio finds it absurd to call Aneta’s father, who lives one thousand kilometers away, but his wife reacted angrily: “only you can live with your mother at ten meters distance!”.

The experience of Aneta seems to be characterized by the rage. Her need to remain “separate” from the arrival environment seems – through a projective identification – to be given to her child, who reacts to the role her mother is forcing on her through her “role responsiveness” (Sandler, 2002), remaining glued to her mother, even when curiosity might urge her to stay on the carpet, to touch the toys and exploring – as she can – the environment.

The marital relationship seems to be locked in an impasse, with great disappointment and anger of both spouses.

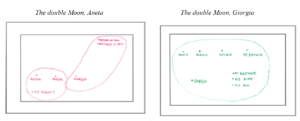

The therapist decides to open a therapeutic space at a new level, the symbolic one, to try to overcome the repetitive quarrelsome sequences of the spouses, and proposes the Double Moon Test, to help the spouses to “see” some of the crucial nodes of the current experience of each of them.

The two drawings show the inability of both spouses to imagine a synthesis between the two worlds, Czech and Italian.

Aneta’s protocol shows the inscription of their child Alexia only in the Czech maternal root that excludes the father, except for a little marginal area; Giorgio’s one shows a unique family, that includes both his new family and his origin family, without any mental space for Aneta’s origin. It is very important to observe that neither of the spouses draws the family constituted with them and their child: Aneta does not place herself and her child in a family with her husband; Giorgio dissolves the new bond in an indistinct space where hierarchies seem not to exist: his wife, daughter, mother and his dead father are on the same line, as well as in the same family space. The symmetry between the drawings makes explicit the angry opposition of the spouses, who do not seem able to meet each other at any level.

The partners realize the absence of their new family on both their drawings; in particular Giorgio is amazed that Aneta does not approve the drawing he has done and comments: “It had never occurred to me to think that our family is another family”. So Aneta can express her difficulty of living with the excessive presence of her husband’s family, while hers is unattainable: “I have to defend myself not to be swallowed. And I have to defend Alexia too”. On his own, perhaps Giorgio had accepted to marry a foreign woman too quickly, with the unconscious hope she would have helped him to somehow distance himself from his original family, but now he seems to think that their marriage in itself represents the greatest possible distance/distinction from his original family, or even a fault he has to be forgiven… Now, according to him, the only problem is Aneta’s adjustment to the current conditions of their family life.

It is possible to hypothesize that also Giorgio is also projecting onto their child his need to normalize their family situation, and his desire for a quick adaptation, so it is impossible for him to tolerate more flexible modalities to take care of her.

Also in the following interviews the dialogue continues starting from the drawings, that constitute, in a certain sense, a “common text”, and both spouses say they are sorry that their project to make a family together has been blocked, although it is still difficult for them to find a common way to meet each other.

After a while, Giorgio agrees that Aneta’s father lives at their home for a period, and Aneta reports that their little girl, with her grandfather, begins to remain on the carpet for five minutes, leaving her free, even though only for a short while…

After some months, during the sessions, Alexia, in her mother’s arms, seems finally attracted by the colours of the pencils that are on the table. It begins to appear in Aneta’s mind the idea of returning to her medical specialization when her child is one year old.

The couple accept to continue their couple therapy…

Concluding remarks

In the two couples presented, formed by an Italian husband and a recently immigrated foreign wife, it is possible to observe that the wives, more distressed than their husbands because they alone live the immigration transition, find a temporary solution to their conflict between their nostalgia for the past and their need to adapt themselves to the new country, through a projective identification of a part of themselves onto their little daughter.

Estela seems to project onto her three-year-old daughter her need to adapt herself to the new reality very quickly, so she claims that her daughter is immediately “autonomous”. On the contrary, Aneta seems to project onto her daughter her own need for a symbiotic relationship, “separated” compared to the surrounding reality.

As always, it is the whole of family dynamics that is decisive. In the two couples described, each husband responds to his wife’s movements in a very different way: in the first case facilitating the evolution of the situation, in the other one helping to stiffen the family dynamics.

The tolerant behaviour – towards both his wife and his daughter – of Estela’s husband, who seems to have reached a good enough individual equilibrium, with a job he likes, and the awareness of having become fully adult and independent from his family of origin, in fact facilitates the evolution of the situation, allowing Estela to recognize her personal difficulties and to ask for an individual help.

On the contrary, the inflexibility of Aneta’s husband, who expects his daughter to stay immediately with others, strengthens the stagnation of the family dynamics. Because Giorgio is entirely blind towards his emotional dependence on his mother and his family of origin, he is set in a symmetrical position with respect to Aneta, who feels compelled to strongly defend her original family and her Czech culture belonging: so in this case both the spouses help to block the situation.

From a methodological point of view, when the couple’s or family’s dynamics appear blocked, it may be useful for the therapist to change therapeutic work register, proposing to the couple or family members what seems the most appropriate among the many tools of expression: psychodrama, spontaneous drawings, drawings with a theme, graphic- projective methods… The data produced through the use of these tools may in fact offer patients a new chance for free associations, metaphors, similes – generally more creative and less repetitive than the usual speeches and worn sequences – because this proposal somehow makes it possible for new elements to emerge, so surprising people and helping them to express even usually silenced preconscious aspects, which can thus be detected by self and the others, opening the way to possible changes (Benghozi, 2014; 2015).

References

Benghozi, P. (2014). L’observation des transformations du spatiogramme de la maison et la figurabilité de l’image inconsciente du corps psychique groupal familial. Revue de psychothérapie psychanalytique de groupe, 63, 2: 147-160. DOI: 10.3917/rppg.063.0147.

Benghozi, P. (2015). Le travail psychique de rêverie et de figurabilité en psychanalyse groupale et familiale. Revue de psychothérapie psychanalytique de groupe, 65, 2: 39-54. DOI: 10.3917/rppg.065.0039.

Darchis, E. (2009). L’instaurazione della genitorialità e le sue vicissitudini. In Zurlo M.C. (a cura di), Percorsi della filiazione, pp. 21-36. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Greco, O. (1999). La doppia luna. Test dei confini e delle appartenenze familiari. Milano: Quaderni del Centro Famiglia, Vita e Pensiero.

Greco, O. (2005). Le test de La double lune en thérapie familial: étude d’un cas clinique. Le divan familial, 14: 137-145. DOI: 10.3917/difa.014.0137.

Greco, O. (2006). Il lavoro clinico con le famiglie complesse. Il test La doppia luna nella ricerca e nella terapia. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Greco, O. (2012). Mediation techniques in Couple and Family Therapy: two clinical vignettes. International Journal of psychoanalysis of couple and family, 11, 1: 25-38.

Losso, R., Packciarz Losso, A. (2006). Divorce terminable and interminable. In Scharff J., Scharff D.E. (eds.), New paradigms for treating relationships, pp.119-131. Lanham: Jason Aronson.

Nathan, T. (1993). Principi di etnopsicoanalisi. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 1996.

Moro, M.R., Neuman, D., Réal, I. (2010). Maternità in esilio. Bambini e migrazioni. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Sandler, J. (1960). The Background of Safety. International Journal of Psycho-analysis, 41: 352356.

Sandler, A.M., Sandler, J. (2002). Gli oggetti interni. Una rivisitazione. Milano: FrancoAngeli.