REVIEW N° 11 | YEAR 2012 / 1

Summary

Mediation techniques in couple and family therapy: Two clinical vignettes

Through the presentation of two clinical vignettes – one from a couple therapy and another one from a family therapy- therapeutic efficacy of utilizing graphic tasks, like graphic-projective instruments (Anzieu, Chabert, 1997), or free children’s drawings or thematic drawings as well, is discussed. Sometimes, in fact, the creation of metaphors both by patients and therapist helps in representing what is unapproachable at a verbal level – because of anguish surplus at the moment – through an allusive technique.

A couple failed three trials of IVF. The holding of the theme of infertility by the therapist allows the couple to mobilize itself towards the external relationships. In a second moment the infertility problems are symbolized by the husband in a very amazing way through a graphic projective instrument (Greco, 2006) in which he traces a sort of “broken penis”. An insight -although weak- about the meaning of his drawing will lead this man to ask an individual therapeutic work some months later.

In a migrant family therapy, the anguishing drawing of the two children about family arrival to Italy allows parents to express their anguish about the recent death of their third son, that obliged them to “fly” away from their country, without any preparation for themselves and for their children.

Keywords: mediation techniques, use of metaphors, graphic-projective instruments, spontaneous or thematic drawings.

Résumé

Techniques de médiation dans les couples et la thérapie familiale : deux vignettes cliniques.

Cette contribution, à travers la présentation de deux situations cliniques – une thérapie de couple et une thérapie familiale- analyse l’efficacité thérapeutique de proposer des instruments graphiques ou d’utiliser les productions graphiques des fils, comme instruments graphique-projectifs (Anzieu, Chabert, 1997), ou bien des dessins libres ou à thème.

Parfois, en effet, la création des métaphores, soit de la part du thérapeute que des patients, aide la représentation de ce que en ce moment-là est inabordable par la pensée, parce-qu’ il provoque trop d’angoisse. Un couple à vécu la faillite de trois fécondations assistées et le thème de l’infertilité vient d’abord accueilli et contenu par le thérapeute, donnant aux conjoints la possibilité d’une mobilisation relationnelle vers l’extérieur, et successivement symbolisé d’une façon surprenante à travers un instrument graphique-projectif (Greco, 2006), où le mari dessine « un pénis interrompu ».

La reconnaissance – même si mitigée- du sens de son propre dessin donnera à cette personne la possibilité de demander un parcours individuel d’approfondissement.

Dans la situation de thérapie familiale avec une famille migrante, le dessin angoisseux des fils par rapport à leur arrivé en Italie permet aux parents d’exprimer leur propre angoisse pour la mort récente du troisième fils, évènement qui les a poussé à « s’enfuir » de l’Amérique du Sud, sans aucune préparation à ce processus migratoire, ni pour soi ni pour leurs fils.

Mots-Clés : techniques de médiation dans le travail thérapeutique, utilisation des métaphores, instruments graphique-projectif, dessins libres ou à thème

Resumen

Técnicas de mediación en la terapia de pareja y de familia: dos viñetas clínicas

A través de la presentación de dos situaciones clínicas – una de terapia de pareja y una de terapia familiar – se analiza la eficacia terapéutica de proponer tareas gráficas o utilizar producciones gráficas de los hijos, como instrumentos gráfico-proyectivos (Anzieu, Chabert, 1997), o dibujos libres o temáticos.

A veces, de hecho, la creación de metáforas, tanto de parte del terapeuta que por los pacientes, ayuda a representar a través de una técnica alusiva lo que en ese momento es inaccesible con el pensamiento, ya que causa mucha angustia.

Una pareja vio fallar tres intentos de fecundación in vitro y el tema de la infertilidad primero es recibido y contenido por el terapeuta, por lo que es posible para los cónyuges una primera movilización relacional hacia el exterior, y más tarde simbolizado en una forma sorprendente a través de un instrumento gráfico-proyectivo (Greco, 2006), sobre el protocolo del cual el esposo dibuja un “pene interrupto”. El reconocimiento – aunque atenuado – del sentido de su propio dibujo llevará más tarde al hombre a pedir una profundización individual.

En la situación de terapia familiar con una familia inmigrante, el diseño angustiado de los hijos acerca de la llegada a Italia permite a los padres de expresar su angustia por la muerte reciente de su tercer hijo, evento que los ha llevado a “escapar” a Sud América, sin ninguna preparación al proceso de migración para sì mismos y para los hijos.

Palabras claves: las técnicas de mediación en el trabajo terapéutico, el uso de las metáforas, instrumentos gráficos proyectivos, dibujos libres o temáticos.

ARTICLE

Mediation techniques in couple and family therapy: two clinical vignettes.

ONDINA GRECO[*]

Through the presentation of two clinical vignettes – one from a couple therapy and another one from a family therapy- therapeutic efficacy of utilizing graphic tasks, like graphic-projective instruments (Anzieu, Chabert, 1997), or free children’s drawings or thematic drawings as well, is discussed. Sometimes, in fact, the creation of metaphors both by patients and therapist helps in representing what is unapproachable at a verbal level – because of anguish surplus at the moment – through an allusive technique.

A couple failed three trials of IVF. The holding of the theme of infertility by the therapist allows the couple to mobilize itself towards the external relationships. In a second moment the infertility problems are symbolized by the husband in a very amazing way through a graphic projective instrument (Greco, 2006) in which he traces a sort of “broken penis”. An insight although weak- about the meaning of his drawing will lead this man to ask an individual therapeutic work some months later.

In a migrant family therapy, the anguishing drawing of the two children about family arrival to Italy allows parents to express their anguish about the recent death of their third son, that obliged them to “fly” away from their country, without any preparation for themselves and for their children. Bianca, 38 years old, and Aldo, 37, married seven years ago, but they cannot have children; the diagnostic tests show a “weak generative capacity” for the husband.

The couple asks for a psychotherapist, after they had failed three attempts of IVF.

Bianca is completely exhausted after this experience: while the first attempt gave immediately a negative result, the other two led the woman to an initial pregnancy, which was interrupted after few weeks, causing her a lot of pain and disappointment. The last attempt, a few months before, was heartbreaking for her. Bianca reports that the powerful hormone treatment, repeated three times, has upset “her basic mood”: she always feels ill, has frequent headaches and cries very easily…

Aldo silently is listening to his wife, then he murmurs: “the second time, when she became pregnant, I thought something for which I feel very much ashamed…I thought that if a baby were born, my parents would have become his/her grandparents and I didn’t want this at all”.

In this way, Aldo leads the therapist to focalize the issue of his relationship with his origin family and the theme of the family intergenerational dimension. The access to parenthood requires a psychological journey to find one’s own family past experience (Darchis, 2009), made up of two identification processes: the first one to search for the child who one has been and who one would have liked to have been – a process that allows the parent’s identification with his/her child; the second one to search for the parents whom one had had and for whom one would have liked to have had – a necessary condition for assuming his/ her parenting role.

During the couple’s interviews the absence of “a mental space for the child” gradually emerges. (Carau, 1995).

On the one hand, the heavy entanglement of the husband-child in his origin family – strengthened by his father’s death, a year before – seems to occupy his psychological world completely. Now Aldo feels responsible for his mother, aged 68, and for his sister, aged 29, also because all their relatives live in the south of Italy and cannot represent a concrete resource, except during the summer holidays. On the other hand, Aldo is trapped in the struggle between his wife and his mother, to which he reacts paralysing himself.

Bianca too brings with herself repeated traumas still looming – her grandfather, an uncle and the dearest of her brothers died in a similar way in three different motorbike accidents within ten years.

“It is as we are under a curse, doctor: have you ever heard a similar story, with always the same accidents?” the woman weeps, while telling the incredible and tragic series of coincidences.

The so desired child in Bianca’s imagination would have put an end to this chain of deaths and sorrows and would have signed a new beginning: also for this his/her lacking is so anguishing for her.

The therapist’s holding of their infertility suffering, more explicit for the wife, more hidden for the husband, makes bit by bit the couple able to open itself to new social relationship, creating a more dynamic life style, more adequate to the partners’ age.

The extreme difficulty of mentalizing feelings and emotions by the partners had already emerged in the first graphical work, through which the therapist had tried to bypass partners’ strong defences.

This involves “The imaginary Couple’s Drawing”, created by an argentinian psychoanalyst, De Parronchi, who worked in a University Clinic for Sterility in Buenos Aires (Marcoli, 2003)

The wife’s drawing shows a couple with infantile and not so sexual features; the husband’s, in which the nearly total absence of sexual differences can be noted (excepted his wife’s hair), even more explicitly talks about his extreme difficulty in recognizing and expressing feeling and emotions directly (the couple has been drawn from behind, as if to go away). The partners are not able to associate anything neither in their own drawing, nor in that of their partner, notwithstanding the stimulus of the psychotherapist.

The symbolization process seems to be blocked for both of them.

An infantile and “fleeing” couple is certainly not able to hold each other’s hand, look in each other’s eyes and “conceive” a child, in the dual meaning of “thinking” and “generating” a child.

In fact the husband presents himself as passive and very dependent on the therapist, from whom he expects indications and solutions, while his wife openly express her anger against her husband, who allows himself to be manipulated by his mother, “as if he were a child”, and against her motherin-law. The wife suggests the possibility of separating more than once, but her husband, nearly paralysed, doesn’t react in any way.

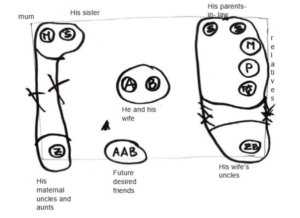

The therapist then decides to work on the distinction process between the origin families and the young family, proposing the graphic projective instrument “The Double Moon Test” [1] to them, in an individual and parallel way. This instrument is aimed to make the subject’s family boundaries and belonging representation emerge. (Greco, 2005)

The test protocol of the wife shows that the distinction between her new family and her origin family has been carried out in her representational world; furthermore some figures of the past are very much in evidence and it seems that Bianca cannot detach herself from these: first of all her dead brother, whose symbol seems to constitute almost the top of a totemic figure, who presides the life of all, even above her parents; then her brother-in-law, from whom her sister divorced some years before, but to whom Bianca says she is still very attached; finally a very dear friend of her before, who, according to Bianca, let their relationship die.

In the right corner, at the bottom of the page, todays’ friends are collocated, more distant and – apparently – less important. The balancing between presence and absence seems to be in favour of the latter: it may be for this reason that there isn’t any space for new arrivals?

However, the woman, with the magic wand, crying adds a child, putting this symbol next to that of her husband, as if expecting the child as a gift from him, and contemporary giving him the responsibility of their couple’s infertility.

The protocol of the husband is, in its final construction, quite disconcerting.

He puts the symbol of the new couple at the center, recognizing it as autonomous from the two origin families, differently from what the therapist had imagined, but the couple, in the finished drawing, appears to be surrounded by two huge “broken” penises.

These symbols are constituted by his origin family on the left: at the top his mother and sister; at the bottom his maternal uncles and aunts, couples who are first placed in an independent family, then joined by a “meta-familiar” circle, which is then rejected and deleted with some crosses.

On the right, symmetrically, he marks his parents-in-law, at the center his brothers-in–law and his wife’s cousins, at the bottom his wife’s uncles, who are similarly marked as two independent families and then surrounded by a “meta-familiar” circle, which is eventually cancelled with other crosses.

The drawing image is so explicit that it almost embarrasses the therapist, but once again the level of spouses’ denial is such that no comment and no association is possible for them both about their own drawing and the other’s, despite several attempts by the therapist to open the dialogue. It is as if for the second time the spouses showed that it was not possible for them to approach the most important emotional nodes openly at this time, so that the therapist calls into question the utility of the couple psychotherapy at this stage.

During the following interview, the spouses talk about Aldo’s mother and sister for a long time, exporting again the problem outside with respect to their bond. At the beginning of the next session, the two partners announce that they want to suspend the sessions as a couple, because Bianca needs a period of “mental rest”, while Aldo says he needs to work on some issues on his own.

It is possible to hypothesize that the recognition – even preconscious – of the meaning of his own drawing has led this man to require an individual path. He is therefore sent to a colleague for an individual psychotherapy, while the therapist remains available for any future deepening at a couple level.

The theme of fertility and sexuality, emerged very clearly for the husband as tied to the relationship with his family of origin, seems to have been secretly themed by the two partners, and they seem to have found the way of mutual agreement not to work on it together, perhaps because they felt it would be too dangerous for them. The short couple psychotherapy could be considered to have made it possible for the husband to face alone the issues that blocked him at a “visceral” level, we could say.

Rolf and his family

The second vignette concerns a family, immigrated to Italy from Chile, constituted by the parents, Rolf and Elvira, both 33 years old, and their children: Hubert, 13 years old, and Isabel, 10 years old.

The family asks a public service, on the recommendation of Hubert’s junior school teachers, who believe that Hubert has severe cognitive difficulties, that are at the base of his isolation and heavy inhibition, according to them. The neuropsychiatric diagnosis, on the contrary, talks about a depressive syndrome, with a very low level of self-esteem that affects boy’s sense of competence and hinders his learning capacity. The neuropsychiatrist sends the family to a Family Consultory. The family, that has been in Italy for 13 months, at the first interview shows a great level of affection and cohesion. The father is a lorry driver for a multinational for which he worked in Chile; the mother as a care taker of an old person for some hours a day. The family arrived in Italy last year and spent some months looking for permanent accommodation, consequently the children started school the following September, so losing one scholastic year.

During the interviews, the children, notwithstanding the papers, feltpens, lego and other games available on the rug, remain immobile on their chairs, polite and well educated like adults.

Hubert replies to be frightened of some classmates, rebellious with the teachers and aggressive with their peers, and his mother adds that in Chile the students are obedient and that she too does not understand how the school works in Italy.

Instead Isabel, that is attending fourth year of elementary school, feels well and has made friends.

The children talk about their day: on their return from school, they find their mother, because she only works in the morning, while their father sometimes stays away for several days, but is always at home at the weekend.

The emotive climate appears controlled: the family seems intent on replying politely and on hiding emotions and feelings, behaviour that perhaps reflects the common effort of adapting themselves to the new country as quickly as possible.

The second interview is dedicated to the theme of their journey and immigration, and the parents say that Italy is a beautiful country, that now that they have work cannot complain in any way, that certainly emigrating is difficult, but gradually things are getting better… the children add that they love playing in the park near their house, where Hubert plays football and Isabel plays ball with her friends… Only asthmatic symptoms that Hubert sometimes presents at school indicate a problem that cannot emerge in the dialogue.

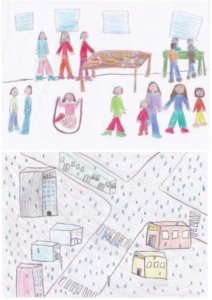

In the third interview, the therapist proposes to the children to draw the last day in Chile and the day of their arrival in Italy.

Isabel uses two papers: the first one represents aunts, uncles and cousins that celebrate together in front of a sumptuously laid table: the children are playing – in particular Isabel is skipping. Her drawing, even if colored with pencils, is animated and lively. The differences with her second drawing are very evident.

The drawing is collocated outside, it is snowing and the family is crossing the road on the zebra crossing one after the other (in Italy it is necessary to be careful and follow the rules!), while another person, unknown to Isabel, is crossing another zebra crossing in an opposite direction to them.

The mother, commenting Isabel’s second drawing, remembers that, when they arrived in Italy, it was snowing and, for them, who were arriving from the Chilean summer, it was very cold so that the mother and children remained closed in a hotel – because they were afraid and because they did not have suitable warm clothing, adapt for the Italian climate. In the meantime, the father was looking for the possibility of accommodation with acquaintances.

The therapist reasons together with them about the hypothesis that Hubert is, from the psychological point of view, still closed inside that hotel, isolated and afraid.

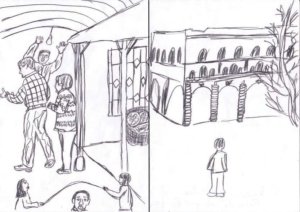

In a same way, Hubert’s drawing is very explicit. He uses one paper, divided into two halves: on the left representing the last day in Chile, while on the right the day of arrival in Italy.

First of all, the formal quality of his drawing can be seen – the sense of movement, the attention to the details, the richness of the represented scene – signal of cognitive capacities quite adequate to his age, but the use of only black pencil shows his depressed mood.

In respect of the drawing content, on the left Hubert draws the farewell party in Chile, in a warm home; the scenery shows persons together in the same room, while two girls and one boy play together with the skipping rope…but at the same time you can note two males, with an expression between enthusiasm and anxiety, that are looking towards the observer, but no one is looking at them. It seems possible to touch the boy’s loneliness in the last days in Chile, perhaps because he was more aware than his sister of the near losses of his point of reference, like relatives, friends, teachers, physical and geographical environment… The right part of his drawing shows the back of a boy, alone, in a street in front of a building. The numerous windows, from which no one is looking out, seem to be eyes by which the boy can feel observed and judged…

Among the free associations of the family about Hubert’s drawing, the father’s one is the most important. He explains that his wife and he decided to come to Italy in a few days, “to flee” his wife adds “from their son Victor’s death”. He was born after two abortions and dead after two and a half months because of an acute pneumonia. Two months later, the father decides to emigrate, he talks to the personnel director of the multinational, who contacts the office in Italy, and guarantees him work, even if at a lower level. His wife says that she saw her husband suffering so much that she did not have the courage to contrast him, even if for her it was very heavy to detach herself from her parents, sisters and brothers-in-law, and to start again from the beginning in a new country, not hers.

The work with the family on their bereavement –commenting together the photos of Victor with his mother, brothers, grandparents and cousins – gradually allows the family to give voice to their traumatic losses – the death of their youngest child/ brother and the event of emigration, that in this context clearly appears as an acting out to escape from the anguish.

Revealing the reason for the decision that brought them to Italy, without any preparation to the migratory process, the father allowed his wife and children to express themselves more freely, and in the end it is also possible for Hubert to take the floor and express his sorrow for losing his cousins and friends, so important for him, already adolescent. Gradually, to the surprise of his teachers, also Hubert’s academic performance is improving…

Discussion

The clinical work in situations characterized by bereavement is complex, for the burden of negative emotions, linked for all members of the family to the issue of “lack”.

Sometimes, the therapeutic work is blocked in moments of impasse, which can find a way out in proposing the couple or the family a new work level, which only apparently move away from the thought and words, to return with new elements and greater resources. It is the case of many expressive instruments that can go from the body involvement, as in psychodrama, to the spontaneous drawing, or drawing about a theme, or graphic projective methods…

Obviously, the efficacy of these types of techniques depends on the adequacy of the clinical analysis rather than the automatic use of the instrument. It is therefore necessary for the psychotherapist to evaluate the most appropriate time to offer the couple or the family a symbolic technique in respect of the current clinical context.

It should be noted how a more effective administration of any symbolic technique registers when at least someone in the family, through his/her words and reflections, shows himself/herself close to the awareness of the issues about which the technique is proposed. Just as much care is necessary for the assessment of what is “produced” and should never be valued as “absolute” data, but should always be assessed in relation to the specific aspects of the context.

With regard to the aspects of content, it is useful to talk with family members, stimulating free associations from the graphic or symbolic product of the technique used, which can offer comparisons, similarities, metaphors, symbolic expressions, loaded with emotional significance. (consider the children of divorced parents in an intense conflict between them, who during the interviews draw spontaneously guns, cannons, machine guns … revealing unambiguously the war between the parents) The therapist, however, has to work with the couple or the family comparing the “clues” which, taken individually, may be ambiguous and whose meaning is to be found in a delicate work of “reconstruction” of the complexity.

Each indicator is in fact, from an abstract point of view, polysemantic, and its meaning is to be unveiled in the specific context in which it is detected.

With regard to the relational aspects, instead, the joint use of a tool or technique, or its individual but parallel use, clarifying that the end products will be discussed together, has the advantage that it typically results in the context of a group.

In fact, the group usually creates a situation that makes expression and self-reflection easier for the different subjects: to be reflected in the other is in effect reassuring, because the other can express before us and for us emotions, feelings and similar experiences.

Also, through the others you can experience what happens if and when a person allows himself/herself to live a greater openness and freedom. The two vignettes of couple and family therapy presented can be considered as examples of the situations in which, for various reasons, the method of free association is blocked and a chronic repetition of speeches and interactive sequences occurs, without being able to reach a meta level which makes them perceptible.

In this case it was necessary to introduce a different register to try to overcome the moment of impasse. In such circumstances, it becomes a crucial step of the therapeutic work to interrupt the automatic sequence of interactions and words, proposing a “task” that surprises the family and invites it on a different ground, somehow not already polluted by repetition, which can be transformed into the basis of new insights. But, as we have seen for Aldo and Bianca, even in front of the most glaring evidence there may be a singular blindness: this indicator is very precious to understand what level of explanation the person is currently able to tolerate and then provides the clinician precise methodological suggestions for managing the situation.

It turns out to be essential for the clinician to observe each subject’s ability to see both what he/she drew, and what emerges from the drawing of the others, using the graphical content of the protocol or the expressive performance for comments, explanations and free associations that can open up unexpected issues – through a sudden insight – or deepen themes already known.

The degree and the quality of the spontaneous reading of the test in coadministration then takes on a character of greater complexity, because it concerns the evaluation of how the couple or family is able to see, in front of the other family members, what the drawing makes explicit about the relationships between them.

At this level the clinician observes with what degree of freedom the family members allow themselves to gather and comment, in front of the others, some relational aspects that the design or the expressive activity, jointly produced, may show very explicitly. On these types of indicators it is possible to base inferences on the degree of freedom and fluidity in family relationships.

The graphic evidence produced in the joint work can in fact facilitate the insight into some of the family members, who becomes a precious ally of the therapist in terms of clarification of problematic issues and opening new spaces in family mental horizon.

In front of the complexity of couple and family, in moments of impasse, doubt, confusion, the proposal of a symbolic technique can facilitate the clinical work, reversing the usual path: from the action and sight to the dialogue and thought, giving symbolic space to what has not had voice and speech yet.

Bibliography

Anzieu D. e Chabert C. (1997), Les méthodes projectives, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

Carau B (1995) Coniugalità, genitorialità e processo della scena primaria, in “Interazioni familiari”, Franco Angeli, Milano, 1/1995 Darchis E. (2009) L’instaurazione della genitorialità e le sue vicissitudini in Zurlo M.C., Percorsi della filiazione, Franco Angeli, Milano, p. 21-36.

Greco O. La doppia luna. Test dei confini e delle appartenenze familiari, Quaderni del Centro Famiglia,Vita e Pensiero, Milano, 1999.

Greco O. (2005) Le test de La double lune en thérapie familial : étude d’un cas clinique, , in « Le divan familial , Revue de thérapie familiale psychanalitique », 14, Printemps 2005, p.137-145

Greco O. (2006), Il lavoro clinico con le famiglie complesse. Il test La doppia Luna nella ricerca e nella terapia, Franco Angeli, Milano. Marcoli A. (2003) Passaggi di vita, Mondadori, Milano.

[*] Psychologist, Couple and Family Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology Service for Couple and Family, Catholic University, Milano, Italia; Paolo Saccani Association, Psychoanalytical Studies about Family and Couple, Milano, Italia, www.associazionepaolosaccani.it ondina.greco@unicatt.it

[1] The Double Moon Test (Greco, 1999; 2006) – useful in structurally complex family situations, like adoptive or reconstituted families, and also in the transition to the constitution of the young couple – is specifically aimed at casting light on the subject’s representations of family boundaries and family belongings, and in addition illustrates the ways in which the subject deals with the element distant or absent. Subjects are invited to draw – in/or outside a rectangle meant to show “their world” – symbols representing those persons and elements most significant for them, and to then enclose within one or more circles those people that belong to the same family, thus creating a subjective representation of the number of families on the scene and of the boundaries of those families (Greco, 2005).