REVIEW N° 19 | YEAR 2018 / 2

Summary

Growing up without a father: the therapeutic work with the dyad of a single mother and her child

In single-parent families, children abandoned by their father before or immediately after their birth, who then bear their mother’s surname, are identified as having an absent father and are identified as lacking this important relationship. Often in these situations mothers, challenged by the absence of their partner from the first months of their child’s life, often tend to try and normalise the situation – in order to avoid re-opening a painful emotional wound for them – yet their children ultimately need to know who their father was and why he left. In the clinical cases to be presented it is shown how during the family therapy with a single mother and child dyad, it is possible to facilitate a process of symbol construction initiated by children which helps them come to understand their family composition and the reason for their father’s absence.

That is, in such situations, one of the tasks of family therapy is to ensure that the therapeutic process allows for the inclusion of the absent father, in the first place in the therapeutic dialogue with the dyad, so that over time it can become represented in the child’s psychological world.

Keywords: single-parent families, absent father, symbolic level, conflicting needs, inclusion of the absent.

Résumé

Grandir sans père: le travail psychanalytique avec la dyade mère célibataire et enfant

Dans les familles monoparentale les enfants – abandonnés par leur père avant ou juste après leur naissance – qui portent le nom de leur mère, sont identifiés comme ayant un père absent et manquant de cette relation au niveau de leur “filiation instituée”. Souvent, dans ces situations, les mères, qui ont dû composer avec l’absence de leur partenaire depuis les premiers mois de la vie de leur enfant, ont tendance à normaliser la situation pour ne pas rouvrir une blessure douloureuse pour elles, tandis que les enfants ont besoin de demander qui est absent et pourquoi.

Pendant la thérapie familiale avec la dyade mère célibataire-enfant, on peut observer un processus de construction de symboles activé par les enfants concernant la question de leur appartenance familiale et l’absence de leur père, comme dans les cas cliniques présentés. Dans ces situations, un des objectifs de la thérapie familiale est d’assurer le processus qui permet l’inclusion de l’absent, en premier lieu dans le dialogue thérapeutique avec la dyade, afin qu’avec le temps cet élément, l’absent, puisse trouver sa place dans le monde psychologique de l’enfant.

Mots-clés: familles monoparentales, père absent, niveau symbolique, besoins contradictoires, inclusion de l’absent.

Resumen

Crecer sin padre: el trabajo psicoanalítico con la pareja “madre soltera e hijo”

En las familias monoparentales, los hijos – abandonados por los padres antes o después el nacimiento – tienen el apellido de la madre, y muestran así una ausencia también a nivel de la “filiación institucional”. A menudo en estas situaciones, la madres, que han tenido que hacer frente a la ausencia del partener desde los primeros meses de vida del hijo, intentan normalizar la situación – para no abrir una herida dolorosa para ellas – mientras los hijos intentan buscar estrategias que les permita hacer la pregunta de quién está ausente y por qué.

Durante la terapia familiar con las parejas madre soltera e hijo, se puede observar el proceso de construcción de símbolos por los hijos respecto a la cuestión de la pertenencia familiar y de la ausencia del padre, como en los casos clínicos presentados.

En estas situaciones, uno de los deberes de la terapia familiar es lo de garantizar que este proceso permita la inclusión del miembro ausente, ante todo en el diálogo terapéutico con la pareja, para que este elemento pueda encontrar un sitio en el espacio psicológico del hijo.

Palabras clave: familias monoparentales, padre ausente, nivel simbólico, necesidades contradictorias, inclusión del miembro ausente.

ARTICLE

Introduction

Children of single mothers, who bear their mother’s surname as they were not legally entitled to their father’s family name, live an anomaly that inevitably influences their level of imaginary or narcissistic relationship with their father (filiation) (Guyotat, 2002). They ultimately need to confront the exclusive relationship (filiation) with their mothers, otherwise they face the risk of a symbiotic drift in that maternal relationship which compromises their development.

It is a wound in their genealogical structure (Benghozy, 2011), since, in addition to their father, they lose contact with their whole paternal family. In most cases, the mothers – who have gone through a very difficult period having had to live the birth of their child and the perinatal period alone – have a strong need to normalise their single-parent family status by actively avoiding the acknowledgement of their partner, (the child’s parent) who has been absent. The child is unconsciously recruited (Sandler and Sandler, 1998) to support his mother’s need for denial by showing that he can mange perfectly well without a father.

At a psychological level there are thus both present and significant absent elements in the family constellation. Psychoanalytic psychology, as it has developed from Freud’s (1899), through to Winnicott’s (1971) and Bion’s (1970) work, underlines the significance of the loss and the permanence of a trace of the absent element in the relational and psychological world at both the symbolic and emotional level, so that some kind of link with the absent remains (Green, 1993).

The father’s absence can thus impact adversely on the process of symbolisation, especially when the child feels the weight of her negative emotions about the father’s absence through her prohibition or resistance to explicitly discussing the topic (Soulé and Noël, 2002). The child who grows up without a father figure as a consequence of his cognitive development, generally during his primary school years, begins to make comparisons with other children, and finds ways of openly raising the issue of who is absent and why (Braff Brodzinsky, 2013).

In the two clinical cases to follow, the children who through drawing – find a ask question about the absence of their father, receive different feedback from their mothers.

Case examples

Paola’s tribe: who’s missing?

Giulia (37 years old) asked to see a therapist after the teacher told her that her daughter Paola (8 years old) started crying because she didn’t want to do a drawing for her grandfather for Father’s Day, as she had in previous years.

Giulia explained, in the first individual interview, that she became pregnant in a relationship, which had just started. Her partner pressed her to end the pregnancy, but she did not want to, and with the help of her family of origin – a very close-knit family – she brought up her daughter on her own, without any contact whatsoever with Paola’s father, who didn’t legally recognize his daughter. The child in fact bears her mother’s surname.

The couple lived on the first floor of a “family” building. In the same building the maternal grandparents lived on the top floor, and the mother’s sisters with their families, on the third and second floors.

The grandparents owned a company, which they managed with their three daughters The strong bond with the extended family seems to have filled the emptiness of the father‘s absence, even if he is still very present in the child’s mind.

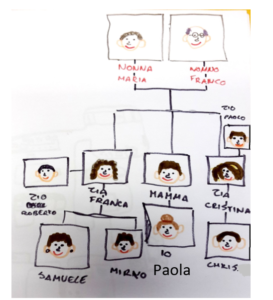

In the first session with the dyad, Paola, surprisingly, asked the therapist: “May I draw my family tree?”

When the child finished her drawing, which highlighted the clear absence of all the fathers, with the exception of the maternal grandfather – the therapist asked: “Is anyone missing in your drawing?”.

Paola’s mother, laughing, immediately answered: “Yes: Aunt Franca’s dog and Aunt Cristina’s cat”, openly showing not only her active defence against the emerging theme of who is missing, but also her support to a scenery in which the only male worthy of the name was her own father, while the others (her sisters’ husbands and her present partner, as we will see) were in fact marginalized.

In the following session, as soon as she entered, Paola said: “last time I forgot something… May I finish my drawing?”.

And she added the Aunts’ husbands. In the drawing all fathers appear beside their mothers, with no relation with their children.

The children are therefore mothers’ children. The only generative couple is the grandparents’ one.

Paola’s father is the absent element, who cannot be represented.

In a following session, Paola’s mother – whose parenting skills the therapist openly acknowledged, given her daughter was so competent and age-appropriate – said she could tell her daughter who her father was, if and when Paola wants. Paola replied introducing the theme of her mother’s partner, Carlo, adding that she felt very sad when, on Father’s Day, she had asked Carlo if she could do a drawing for him, but he replied: “I’m not your father, you already have a father…”.

This prevented her from leaning on a substitutive paternal figure. Giulia said she knew where Paola’s father was living but that she had never looked for him, because he had never cared for his daughter in any way. The therapist asked Paola if she wanted to write a fantasy letter to him? After thinking about it a little while, the child replied she would like to write it to Carlo, with whom together with her mother she has been having fantastic holidays for two years, visiting different countries around the world.

Paola spoke about a school friend of hers, Liù, born in China but adopted by an Italian couple. She spoke with the therapist about the fact that sometimes it happens that children’s parents cannot take care of their children, and so they find new parents, without though forgetting the first ones.

Towards the end of the therapy, Carlo moved in to live at Giulia and Paola’s house, and the child during the last session said that once she even got confused and called him “daddy”.

Marco and his foreign father

Rosa asked for help because her child’s teachers reported that Marco, 8 years old, was very restless. He disturbed his classmates and refused to work if the teacher did not let him stay close to him.

Marco is the son of Rosa (45 years old) and of a man from Ecuador, whom he has never met, but with whom he shares the same black coloured hair and amber skin.

In a first individual session, Rosa hurriedly reported that her relationship with Marco’s father left her three months after they met. She said that her partner, who had never had a permanent job and changed residence very frequently, went away, even though he knew that Rosa was pregnant. She decided to continue her pregnancy alone. Rosa also reported that Marco’s father had just returned, telephoning her and asking her to meet their son. She said that she absolutely refused to allow this meeting, because her ex-partner is completely unreliable. She noted that he would often say he wanted to do something but change his mind a few days later.

Rosa lives in a town a few kilometres from her old parents’ house. Her mother had previously had a stroke, for which she was hospitalized for four months and had recently come back home, to the care of her husband. When his grandmother was in hospital, Marco asked his mother to stay at his grandfather’s home to sleep and his mother agreed, because he goes to school near his grandparents’ home. Rosa noted, “this solution was more convenient for everyone”. Rosa usually has dinner with her parents, and when it is bedtime, she puts Marco to bed there and then goes home. Marco is thus living with his grandparents, one of whom needs intensive care, and the therapist feels that Rosa is actually leaving her old parents to her 8-year-old son!

During the sessions, the child appears very affectionate and he seems to need to be seen. The meeting with Marco’s teachers confirmed that Marco is a very clever child, who has found ways to attract his male teacher’s attention.

Rosa was able to understand her son’s material needs particularly his need for new clothes every two months, because he was growing so fast, but she seems completely unaware of Marco’s emotional needs especially to live in a situation adequate to his age and needs.

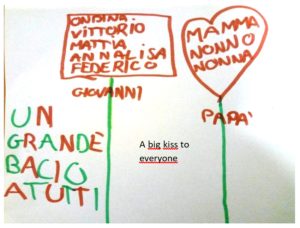

Rosa says that Marco could not miss his father because he has never met him. The therapist’s feeling is that Rosa, speaking about her son, is in fact, speaking about herself. In the session Marco gives the therapist the drawing below.

The child explains that Giovanni is a school friend who was in his class the previous year, but moved to Switzerland, where his father works. He went to see his classmates in December: “so, sometimes he is here, sometimes not”, concludes Marco, placing his father in a position similar to that of this classmate.

The therapist’s name appears together with those of his classmates, and the sentence “a big kiss to everyone” shows that the child feels the duty to reassure his mother and adults in general about his loyalty and trustworthiness.

The child expresses his wish to draw his father, and to his mother’s surprise: “you have never seen him!” he replies: “I’ll draw him with black hair, like me”. The mother shows him a photograph of his father, whom the child really looks like. The mother tells her son that when he is grown up, he will be able to choose whether to meet his father or not, but, at present, for her, the discussion is over. This seems to be the first time that Rosa has realised that her son may have needs different from her own. Marco, it seems, does not have anyone close to him who can somehow represent his absent father, because his mother does not have a partner, not even friends. She says that she does want any such relationships. At school there are only female teachers. Together with Rosa – about whom the therapist underlines the struggle of a life dedicated to her son and her job – the therapist tries to think about situations in which Marco could find male figures who could help him in his development. Rosa admits that her own father, now old and totally dedicated to his wife’s care, can only dedicate a very little time to Marco. Exploring community resources with Rosa, a scout group was found, which was accepted by her but only after some procrastination. This group opened up a new world to Marco. He found other families that invited him for dinner, and after a while even to sleep at their homes!

It was impossible in this case to address directly the right of the child to ask about his father and express his emotions about him. Nevertheless, the mother could accept her son’s larger relational world allowing him to get out from the claustrophobic horizon which he had been closed into, in her turn opening up, albeit at the initial level, to some new interactions.

Discussion

There are three common themes in the two cases presented. The first crucial element is that in both cases the mothers ask for help when the children start presenting symptoms – Paola at an emotional level, Marco at a behavioural one. The symptoms refer to the break of their role-responsiveness (Sandler and Sandler, 1998): until that moment the children had been faithful servants of their mothers’ need to think: “there is no problem if your father is not here”. The children’s growth, the development of their curiosity and operational thought, reopened the issue of their father’s absence, one which previously it seems, remained in the shadow.

Further, the position the therapist took, resulted in the construction of a kind of a psychological Russian doll whereby the recognition of the mothers’ needs came first resulting in them becoming more able to recognise their children’s needs.

The therapist’s countertransference – her empathy towards the “internal child” of the mother, recognition and enhancement of child’s ability to be in the relationship – also helped to lead the clinical intervention. It also managing to avoid two risks that would have sabotaged the therapy. Firstly it managed the risk that the mother could have felt the therapist had appropriated her role as the “good mother”, depriving her of her own role (competition with the therapist) and on the other hand the risk that the therapist was mainly concerned with the child, who could have been seen by his/her mother as a rival (competition with her child).

The therapist’s support to the dyad, directed first of all at supporting the mother, enhancing the positive aspects of the situation and recognising the mother’s needs, helped the situation to evolve in both cases presented.

The third common point – particularly relevant to the children – refers to the usefulness of facilitating the symbolisation of emotions and thoughts through play and drawing.

As Tisseron (2000) wrote, symbolisation through images, halfway between the body and verbal level, represents a step forward in the process of symbolisation. This symbolisation acts as mediator to the figurability of the filial bonds, when there is a flaw in the genealogical container (Benghozi, 2003). It is very difficult to deal with the preconscious level of the structuring of filial bonds and the permanence of the link with those who are absent, if there is no symbolic code that allows access to them. It is very important to emphasise the children’s ability to introduce explicitly the crucial theme of their absent father – that mothers because of their own needs would like to censor – which implicitly urges a focus on this absence, in order to find a sort of repair (in Benghozi’s terms, to recreate the fractured network of bonds with a new narrative container).

The aim of the psychoanalytic family therapy is to help family members to recognise and accept their preconscious emotions, thoughts and feelings that infuse their relationships and to look for more suitable solutions to the life-cycle phase they are experiencing. This leads to new questions and needs, especially in the children as they develop and their curiosity grows. Such interventions however, need to take account the degree to which change can be tolerated by the parent, whilst remaining focused on the goal of preventing the explosion of more severe symptoms during adolescence.

References

Benghozi, P. (2003). Esthétique de la figurabilité et néocontenants narratifs groupaux médiations d’expression. Revue de psychothérapie psychanalytique de groupe, 2, 41: 7-12.

Benghozi, P. (2011). Maillage, Démaillage, Remaillage psychanalytique des liens. International Review of Psychoanalysis of Couple and Family, 9, 1: 74-85.

Bion, W.R. (1970). Attention and Interpretation. London: Heinemann.

Braff Brodzinsky, A. (2013). Can I tell you about Adoption? A guide for friends, family and professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

Freud, S. (1899). L’interpretazione dei sogni. OSF, vol. 3. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 1989.

Green, A. (1993). Il lavoro del negativo. Roma: Borla.

Guyotat, J. (2002). La struttura del legame di filiazione. In Zurlo M.C. (Ed.), La filiazione problematica, pp. 73-114. Napoli: Liguori.

Sandler, J., Sandler, A.M. (1998). Internal Objects Revisited. New York: International Universities Press.

Soulé, M., Noël, J. (2002). Aspetti psicologici delle nozioni di filiazione e identità e il segreto delle origini. In Zurlo M.C. (Ed.), La filiazione problematica, pp.253-254. Napoli: Liguori.

Tisseron, S. (2002). Il cane e l’ombrello. I processi di simbolizzazione tra le generazioni. In Zurlo M.C. (Ed.), La filiazione problematica, pp.115-126. Napoli: Liguori.

Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock Publications.